Christina Hnatov and I walked across the University of Maryland campus to grab bubble tea, chatting about knitting, grading, birding, the solar system, and course assignments. This was typical for our conversations: jumping from topic to topic, sharing things that caught our attention in an unstructured idea exchange.

That summer, we shared things like the podcast episode: Choose to be Curious: The Art of Noticing with Rob Walker, a New York Times article about How to avoid awkward holiday conversations by Jancee Dunn, a Brené Brown podcast episode featuring Esther Perel about artificial intimacy, and a YouTube video about How to do nothing from Jenny Odell. it didn’t take us long to amass a whole pile of ideas.

We felt compelled to do something with those ideas. Christina shared that she wanted to make a class about curiosity. I had a desire to design a new class, and our department embraced associational and divergent thinking as ways of working, giving us the space to explore connections between unrelated ideas and embrace non-linear thinking.

We started small, not wanting to commit too much time to an experimental, ambiguous idea, and pulled from our design background of trying out ideas quickly and in low-resolution ways. In late September 2024, we added a weekly meeting to our calendars called “[plan] New class.” There was no concrete course idea, just vague notions of the concept of curiosity mixed with the impact of technology on critical thinking, and thoughts from our idea exchange to give us some inspiration.

We opened a blank Mural, a digital whiteboard space, and captured the concepts that resonated most with us: what makes a meaningful connection, small talk to build communication skills, experiencing life through our phones, and individualism vs. collectivism. We also added a spot in the Mural for all of the things we collected in our idea exchange. We labeled this “Connected tangents?”, unsure of how everything would fit together, but wanting to leave space for emergent ideas that could eventually lead to unexpected inspiration.

For weeks, this “new class” was a volley of “what ifs…” and “yes, and’s…” still with no clear focus. We were in possibility-mode, allowing ourselves to dream big and releasing ourselves from the constraints of what a class should be: What if this class felt like a book club? Wouldn’t it be cool if we could somehow bring in birding? Does exploring the sense of wonder have a place here?

Our nebulous brainstorm hovered around the ideas of human connection and technology, but Christina and I found ourselves wondering if we were the right people to teach it. We could make a class about those concepts, but we weren’t convinced were the right fit based on our knowledge and expertise, which focused on design and innovation.

Weeks into planning, a New York Times article made its way to our inboxes: How to Add More Play to Your Grown-Up Life, Even Now. This was the inspiration we needed to put the class into focus. Play was a topic we could connect with on a personal level through our shared curiosity. Play was something we knew well because of our design work, where low-stakes experiments and playful brainstorms are essential for our work. Play was (and still is) a way of working for our department, the Academy for Innovation & Entrepreneurship, focusing on serious play to collaborate effectively as a team and with others.

Our confidence and excitement reinvigorated, we shifted the focus from connection and technology to connection and play. As a department, we were curious if students would be interested in exploring these concepts through a design lens, and this was an opportunity to engage more directly with students who don’t necessarily identify as innovators or entrepreneurs. With that in mind, we moved from possibility-mode to experiment-mode and began quickly testing different aspects of the course.

We brainstormed course names and shared them with students to get feedback. Top contenders included The Human’s Guide to Connecting, 500 Friends but No One to Feed Your Cat (inspired by the Brené Brown podcast), and Noticing the World Around You. We also had many that didn’t make the cut: How to walk without headphones, Undesign your purpose (a riff on another class we teach called Design Your Purpose), and The Courage to Connect.

For each name, we asked students what they thought the class was about and if they would sign up for it. Many names were met with curiosity, but none had the excitement we were hoping for. 500 Friends but No One to Feed Your Cat received the most intrigue, but we realized it was focused on connection, and the play piece was missing. We brainstormed variations of it and tested those with students. Within a week, we settled on our course name: IDEA360: 500 Friends but No One to Play With.

For each name, we asked students what they thought the class was about and if they would sign up for it. Many names were met with curiosity, but none had the excitement we were hoping for. 500 Friends but No One to Feed Your Cat received the most intrigue, but we realized it was focused on connection, and the play piece was missing. We brainstormed variations of it and tested those with students. Within a week, we settled on our course name: IDEA360: 500 Friends but No One to Play With.

This low-stakes way of testing a course name helped us learn quickly and gain confidence in the resonance of this course idea with students.

We drafted a syllabus outlining major assignments embodying connection and play from a design lens, like a bingo card. Each square would have a quick activity prompting students to try out different course concepts around connection and play, like frolicking through the field for two minutes, going for a walk without any technology, and making small talk with a stranger while waiting in line.

With a name and the syllabus, we were ready for the ultimate test: Would students actually sign up for the course? We added it to the Spring 2025 course schedule and waited to see if students would enroll. We wanted to fill up half of the seats in this 20 seat class before committing to offering it.

We hit our threshold by early December and changed the name of our weekly planning meeting to “IDEA360 planning.”

We revisited our Mural to add a large post-it to the top that read: Book club, playdates with fieldwork mixed in, as a reminder of our course vision.

To embody a book club feel, where people freely share thoughts on a shared reading, we found readings, videos, and podcasts to provoke student reactions and coax class conversations. We also searched through our pile of “Connected tangents?” for fieldwork ideas so students could try out and reflect on class skills. We pulled the idea of a “noticing” walk from Rob Walker’s podcast Choose to be Curious: The Art of Noticing for students to practice observation skills. The fieldwork assignment would prompt students to pick one thing to notice, like security cameras, the color blue, or things shaped like triangles, and go for a walk to count how many they could find.

We made sure each component linked back to the learning objectives.

We built out the major assignments and created the grading structure.

We designed a visual theme and color-scheme for the course.

The course was taking shape.

With the building blocks of the course in place, we began designing the course more granularly, planning it week by week. We started with the first three weeks of the course to ensure we would be ready for the start of the semester, and made the decision to build the remaining weeks as the semester progressed to allow space for emerging ideas and adjustments based on student feedback. We kept things loose and nimble, even at this detailed level, viewing it all as an experiment with something to learn.

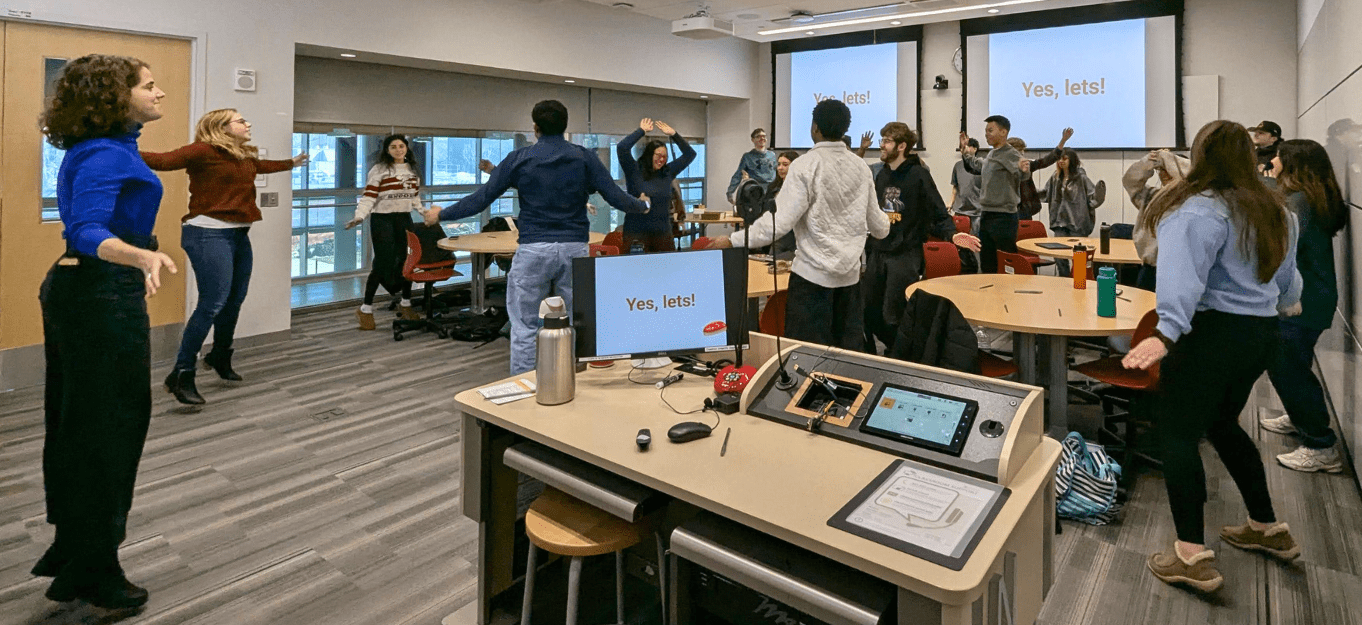

The first day of class came, and we were ready with brown field guide notebooks for each student, a plan for the first three weeks, and anticipation to meet our students and see how the course would unfold.

Almost immediately, we had to make adjustments: changing due dates to better meet the students’ needs and adding accountability submissions to prompt students to engage with the provocations before coming to class. This was expected and welcomed – we had room for that. This was an experiment, after all, a space to be curious, explore ideas, learn in real-time, and play.

Almost a year later, we are offering the course again this coming Spring 2026 semester. The first offering was a strong and nimble prototype that led to lots of learning. We learned that giving students something to read isn’t enough to provoke conversation; part of designing a playful course also means designing assignments so that they’re fun and interesting to grade, and it’s always helpful to explicitly state and restate (and restate again!) how the content is connected.

Just as connection and play can be explored through a design lens, designing a course can be explored through connection and play. We learned that curiosity, holding space for emerging ideas, and designing through experimentation is not just fun; it’s an effective method for building something relevant, engaging, and a bit unexpected.